This is the second essay in the Anxiety Algorithms series. Click here to read Part 1.

A paranoid is someone who knows a little of what’s going on. William S. Burroughs

When I ran Hipmunk, I would often feel like small setbacks meant disaster. When our first employee quit after a few years, I worried everyone was about to quit and that we’d never recover.

That didn’t happen. Later, I spent some time trying to better discern which of my fears were founded.

I came across a model in the immune system, which constantly deals with uncertain and potentially deadly threats. The more I learned about it, the better I’ve understood anxiety, disease, and the subtle tradeoffs of fighting both—and the less stressed I’ve been.

Immunity and Recognition#

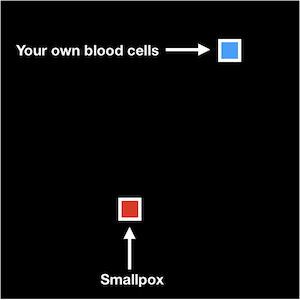

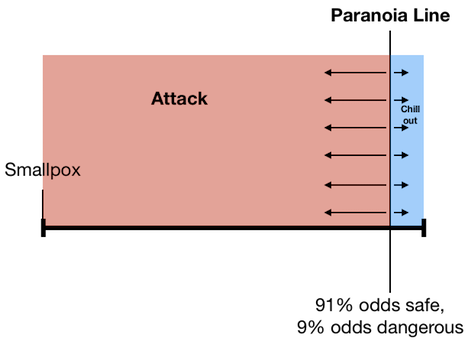

When your immune system encounters something new, it gets “classified” as either a threat or non-threat based on past experience. Your blood cells are good for you, but after you receive a smallpox vaccine, you’re primed to attack any smallpox viruses:

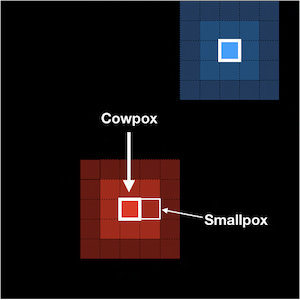

Your don’t even need an exact match. Louis Pasteur realized that deliberately infecting people with cowpox (a mild sickness) gave them immunity to the similar but more deadly smallpox[1]:

Responding Under Uncertainty#

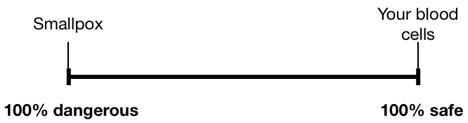

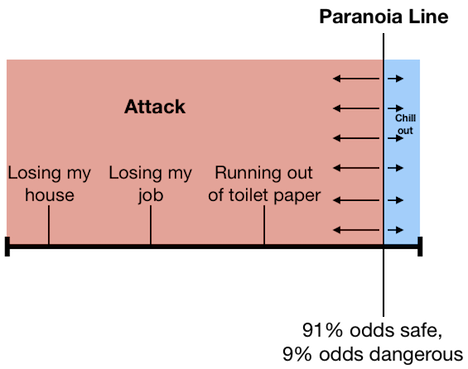

Anything you encounter has a likelihood of being dangerous along a continuum:

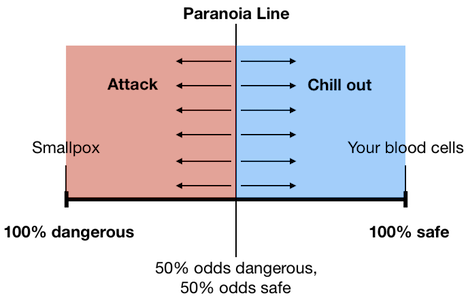

You need to draw a line of where to react, which I call the Paranoia Line:

The existence of a Paranoia Line helps your immune system keep you safer by attacking more-likely threats and not less-likely threats. But choosing where to draw the line is ultimately an engineering decision, and one with profound implications for our survival.

Assume that when you react appropriately to either a threat or non-threat, you survive, and that if you ignore a real threat (e.g. cancer), you die.

What if you attack something that’s good for you—say, your healthy skin cells? You might itch, but probably survive. But not always; if you attack your healthy heart cells, for example, you're in trouble. So let’s assume you have a 90% chance of survival when you attack a good thing[2].

You can put this all in a payoff matrix:

| It’s a threat | It's not a threat | |

|---|---|---|

| You attack | 100% survive | 90% survive |

| You don't attack | 0% survive | 100% survive |

For this payoff matrix, the best line is around 91% safe[3]:

The Painful Tradeoff#

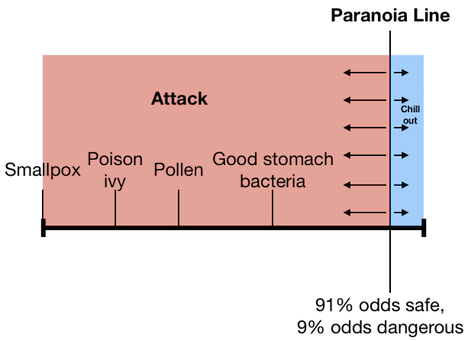

Having a high Paranoia Line helps keep us safe, but it also means accepting a high rate of false positives, where our body attacks things that aren't actually threats.

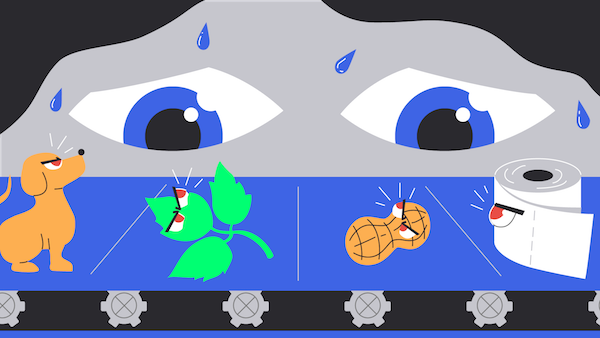

Many common ailments fit this category: rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, ulcerative colitis, eczema, and allergies, among others. In a sense, these conditions are the tax our bodies pay for erring on the side of attacking real threats[4]:

The Life and Death Tradeoff#

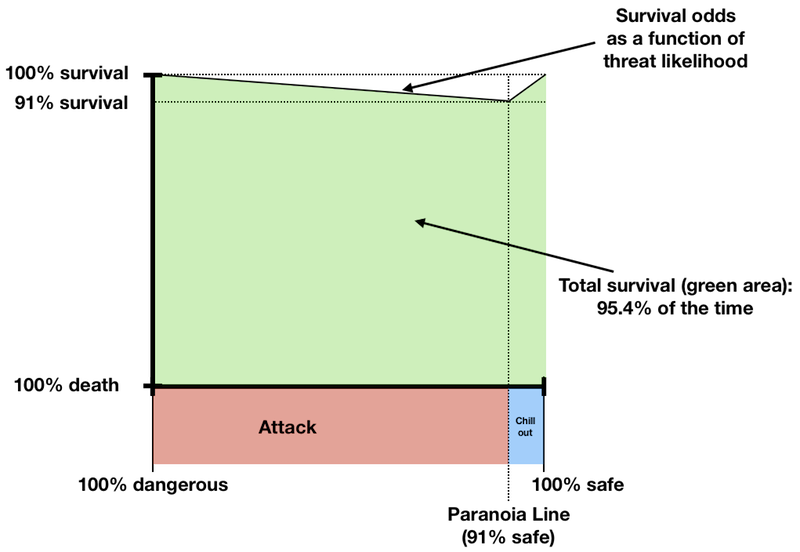

How well will this Paranoia Line keep you safe?

It depends what it’s reacting to. When something is 100% safe or dangerous, you react appropriately and always survive.

But consider something that has an 80% chance of being safe. You attack it because it’s in the red zone. But 80% of the time it’s safe! And in those cases, you only survive 90% of the time. So your odds of survival in this scenario are only 92%.

Here’s a plot of survival odds for all threat likelihoods:

Across all threats, you survive 95.4% of the time.

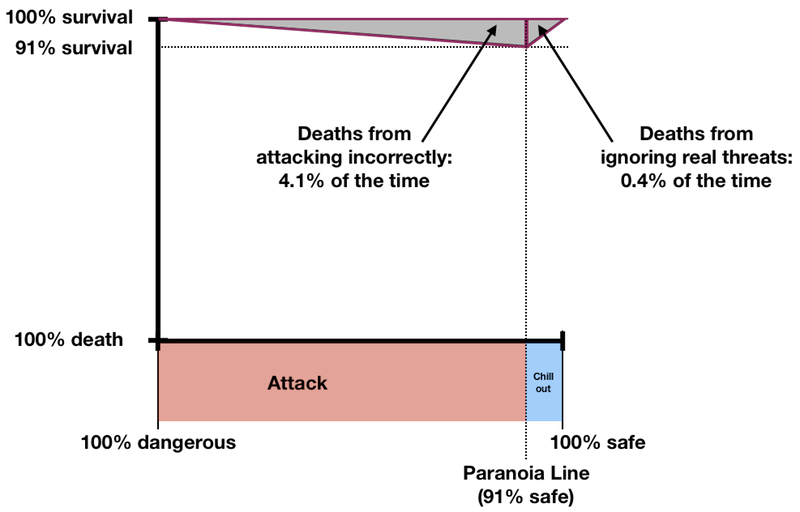

Now here’s where the deaths happen:

There are many more deaths from attacking incorrectly. Said differently, when safety is at its maximum, most death is self-inflicted—a result of overreaction[5].

Let’s look at a real example from the COVID-19 pandemic. Nobody’s body recognizes the new virus, so we err on the side of attacking. This means most survive, but when people die, the death usually seem to be a result of the body’s reaction to the virus rather than the virus alone:

For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, some people—especially the elderly and sick—may have dysfunctional immune systems that fail to keep the response to particular pathogens in check. This could cause an uncontrolled immune response, triggering an overproduction of immune cells and their signaling molecules and leading to a cytokine storm often associated with a flood of immune cells into the lung. “That’s when you end up with a lot of these really severe inflammatory disease conditions like pneumonia, shortness of breath, inflammation of the airway, and so forth,” says Rasmussen. [Emphasis mine]

Fear and Uncertainty#

Suppose you were designing a robot to navigate complex threats. You’d have it imagine possible futures and guide its action based on past experiences. Then you’d draw the Paranoia Line where the overall odds of survival are maximized.

This would entail the same kinds of tradeoffs as the immune system. The robot would err on the side of worrying about most things—including things with only a small chance of being real threats—and would therefore be prone to phobias, paranoia, and anxiety.

And most of the time the robot died, it would die by overreacting to non-threats.

Imagining the Human Algorithm#

Humans aren’t robots, but if you imagine our brain “running this algorithm,” some things become easier to reason about.

Why everyone has some anxiety#

Having a high Paranoia Line provided a major survival advantage to our ancestors. So despite the downsides, we’re calibrated to err on the side of overreacting to uncertain threats.

Why different people have different anxieties#

Our anxiety responds to the likelihood something is a threat, but there is no universal way to know how likely anything is. Instead, we each rely on our own matrix, which is colored by previous experience.

Why now is especially anxious#

Our propensity to fear the worst is emotionally challenging during normal times, but these days we’re being presented new, previously-unknown things constantly.

Because the unknown is uncertain, your anxiety dutifully gets worked up preparing to respond. If you’re responsible for others, it’s even harder, because you’re thinking of ways to keep them safe too[6].

Calming Anxiety#

The good news is that understanding anxiety in this way also suggests several techniques for reducing anxiety without endangering ourselves.

Perspective#

It’s normal to feel that when you’re anxious, there must be something wrong, but this is not necessarily true.

Don’t just ask yourself “What should I do about this thing I’m stressing about?”

Also ask, “Is stressing about this thing making me incorrectly perceive it as a threat?”

Doing this can help you get at the likelihood something is actually a threat, which can allow you to dedicate a more appropriate amount of time and energy to it.

Mental vaccination#

The best way to protect yourself against smallpox is to get vaccinated, and the same is true for anxiety.

I used to be anxious about the possibility that my first startup, BookTour, would fail. When it actually failed, I was sad for a few days; then I moved on with my life.

This provided partial immunity. When later I had the thought, “if Hipmunk fails I’ll never be happy again,” I remembered I used to worry that way about BookTour and it wasn’t true.

When you fear imminent disaster, remember other times you’ve felt that way that have turned out ok.

Re-assessment#

The possible futures in your mind are colored by experiences you’ve had in the past. The more red in your matrix, the more kinds of futures will be scary. Things can be red because they’re actually threats, or because you encountered them during a stressful time (like running a company) when almost everything seemed red.

However, you can choose to re-color your matrix by making it a point to express gratitude. There’s evidence that this increases mental well-being and even physical health.

Feeling gratitude doesn’t mean naively convincing yourself everything scary is actually safe. Instead, it means applying a more positive context—a blue tint—and seeing what’s still red. Those are the things worth your attention.

Final thoughts#

Most successful founders don't talk about their big mistakes. This used to make me feel worse, because making big mistakes felt like proof of my not belonging to the Successful Founders Club.

Then I learned that even critical systems like our immune systems make mistakes all the time.

When you feel bad about your mistakes, remind yourself, “mistakes are inevitable when responding under uncertainty.” And know that it's not mistakes that separates successful founders from others; it's how they react and learn.

In my next post, I show how you can move the Paranoia Line.

Thanks to my pre-readers for their helpful comments: Andrew Wansley, Brian Christian, James Somers, Kelly Peeler, Nancy Hua, Sanjay Sarma, Shirley Wang, Steve Huffman, Uri Lopatin, and Zak Stone. And thanks to Yuval Haker for the illustrations.

Footnotes#

The word “vaccine” comes from the Latin word for cow. ↩︎

The exact number isn’t relevant; it’s that the consequences of missing a real threat are more dire than attacking a non-threat. ↩︎

Let:

T be the likelihood that a given thing is a threat

a(T) be the probability of survival when attacking it

c(T) be the probability of survival when ignoring it

Combine the payoff matrix with the likelihood it’s a threat (T) or non-threat (1-T):

a(T) = 100%T + 90%(1-T) = 0.1T + 0.9

c(T) = 0%T + 100%(1-T) = 1-T

The Paranoia Line is the T where attacking and ignoring have identical survival likelihood:

a(T) = c(T) = 0.1T + 0.9 = 1-T

1.1T = 0.1

So the Paranoia Line is where something has a 0.1/1.1 ≈ 9.1% chance of being a threat, or ≈90.9% of being safe. ↩︎Our propensity to attack uncertain things has other benefits, however; it’s why vaccines protect us against similar-enough viruses and bacteria. ↩︎

Under certain simplifying assumptions, including:

(1) That threat likelihoods are uniformly distributed, i.e. that the chance of encountering something that’s 20% likely to be safe is the same as encountering something that’s 50% likely to be safe and 80% likely to be safe, etc.

(2) That the perceived threat likelihoods are accurate (e.g. that if your body perceives something as 20% likely to be a threat, it actually has exactly a 20% chance of being something that kills you)

(3) That a given thing is either a threat or not a threat (with no possibility that it’s helpful in low quantities and dangerous at high quantities)

These assumptions aren’t all true in most cases. But the core tradeoffs between overreacting and underrating still arise some of the time in almost any scenario with uncertainty. ↩︎The tendency to fear the uncertain operates in these relationships, too—turning misunderstandings into heated conflict. ↩︎